Foreword

by Professor Ronald Hutton

The civil wars of the 1640s were probably the worst experience that the people of the British Isles have ever undergone. Epidemics of disease killed far greater numbers of human beings in a shorter time than these conflicts ever did, but left people’s sense of their world, their religious, political and social beliefs and their relations with each other, more or less intact.

The civil strife destroyed all of those things. England went through three civil wars between 1642 and 1651, of which the first and biggest, which ended in 1646, killed about 100,000 people outright in a population of just five million, and left about another 150,000 to die by inches of wounds, while in battle-torn areas civilian burials rose far over the average as illness, hunger and poverty all increased amid local economies wrecked by the fighting. Trade was disrupted all over the nation, and crushing war taxation ground down incomes further, so that even communities which never heard a shot fired in anger went into deep economic recession. Those in war zones had houses and crops burned, and livestock slaughtered or stolen.

Perhaps a quarter of the entire adult male population of England served as soldiers at some point in the Great Civil War, a degree of militarisation never experienced before or since, just as the loss of life was the greatest ever known as a percentage of the people, dwarfing that in the World Wars. This was no war between states, as in America in the 1860s, because across the nation virtually every district was divided between rival partisans, and the fault lines of ideological hatred ran through villages, households and families. This really was a conflict in which fathers fought sons, brothers against brother, and mothers and children disowned each other. The ideas for which they contended amounted to different visions of how the Church, the political system and the social order should be, and in an important sense England has never recovered from the clash.

Ever since, what was formerly a largely united and consensual nation has been divided between two political parties representing different senses of what it means to be English, and a Church which had commanded the loyalty of all but five per cent of the population has been shattered into large numbers of nonconformist Protestant denominations, such as Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Baptists and Quakers. Ever since then, also, Parliament has been an essential and almost constant component of political life, providing an arena in which differences of opinion can constantly be expressed.

The effect on Scotland and Ireland was proportionately more dramatic. The loss of life in the civil wars there was even worse (a fifth to a third of all the Irish dying), and it left the self-confidence of Scotland shattered, leading subsequently to a union with England which is only now unraveling, while a Protestant Ascendancy was imposed on Ireland which endured until 1922 and remains in a bitterly divided north of the island.The Civil War therefore deeply matters, and part of the excitement of learning about it derives from the fact that it was at once a national conflict and a patchwork of local struggles. As such, it combines the interest of the grand epic and the kitchen-sink drama.

As a county, Dorset shared, and suffered, to the full in both aspects. It had the unhappy characteristic of being one of those areas which were contested between the two parties, lying in a frontier zone between their core territories. It also has another grim feature, of being involved in action throughout the war, from the siege of Sherborne Castle in 1642 to those of Corfe and Portland Castles in 1646. It was never granted a moment of reprieve from the violence, and its rich farmlands and its ports, so strategically sited for the overseas trade to which both sides looked for income and military supplies, made each part of it a rich prize.

Such was the fate of the circle of communities centred on Weymouth, the only port which the royalists managed to capture and hold for a significant length of time. They passed from the hands of one party to another in a succession of episodes of violence. Each was divided internally, between royalists and parliamentarians. For a time in 1645 the twin towns of Weymouth and Melcombe were in different hands, and Weymouth became a battlefield, and even when they were reunited in the cause of Parliament, Portland held out for the king, into another year.

The struggle for Dorset threw some of the personalities who engaged in it into high relief, making them national heroes and villains, such as Sir Lewis Dyve, the diehard royalist commander, William Sydenham, who became one of Oliver Cromwell’s Council of State as Lord Protector, and Anthony Ashley Cooper, the savage and supple schemer who, after various changes of side, grew into one of the leading politicians of the later seventeenth century.

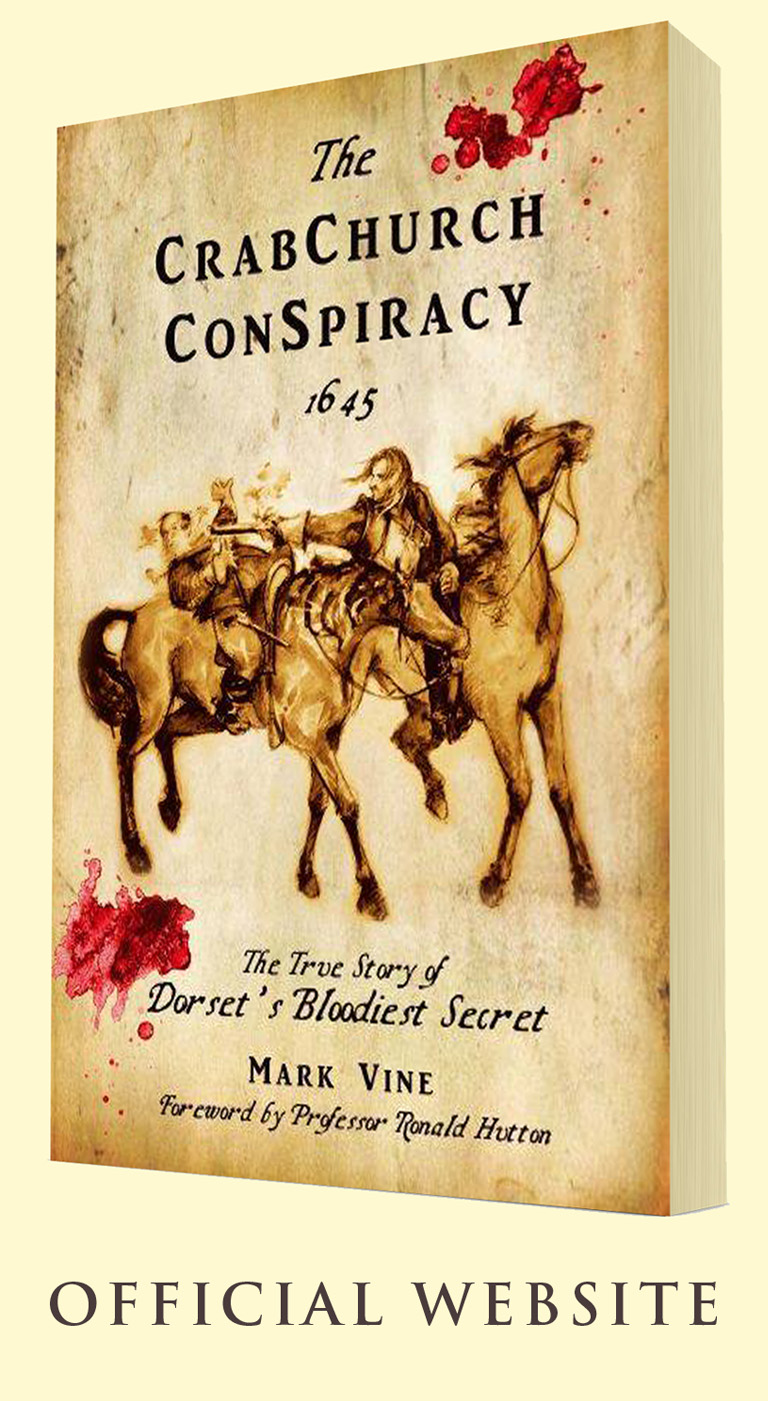

Mark Vine’s new edition of his already well-loved book, “The Crabchurch Conspiracy”, is the best work ever written about the dramatic events in and around Weymouth during the war, and the rise to prominence of the Sydenham family which they produced. It is built on the greatest depth of research yet carried out into them, including texts in which the people who shared in those upheavals speak vividly of the hopes, hatreds, horrors and raptures which they experienced. Mark clearly has his own favourite characters, but throughout does justice to all involved, from the leaders of events to nameless soldiers who emerged from the struggle as victors or found an unmarked grave in the hillsides and fields around the town or were lost forever choking in the waters of its harbour.

This is a work which brings properly to life the most dramatic and horrific sequence of experiences which this town has ever known, and which put it, at moments, at the heart of England’s destiny.